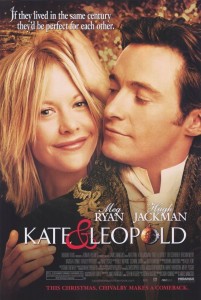

Movie Review: About Last Night

The 1986 Brat Pack romance About Last Night is one of my favorite films. That movie was adapted from the 1970s David Mamet play “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” and starred Rob Lowe and Demi Moore as Danny and Debbie — two young adults trying to make a relationship out of a one night stand. Strong comedic turns from James Belushi and Elizabeth Perkins as Bernie and Joan, the lovers’ best friends, added a great deal of enjoyable humor to the film.

The 1986 Brat Pack romance About Last Night is one of my favorite films. That movie was adapted from the 1970s David Mamet play “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” and starred Rob Lowe and Demi Moore as Danny and Debbie — two young adults trying to make a relationship out of a one night stand. Strong comedic turns from James Belushi and Elizabeth Perkins as Bernie and Joan, the lovers’ best friends, added a great deal of enjoyable humor to the film.

I have watched that 80s film so often that when I saw a trailer recycling its one-liners I was appalled…until I realized that film was a remake. Knowing the original film was dated I was actually happy with the idea of a remake, bringing that movie’s charm to a new generation of young adults. Last year around Valentine’s Day couples again had a chance to talk About Last Night.

I was surprised, however, at how closely this 2014 version hews to the original. The plot is beat-for-beat the same, with many scenes being re-enacted with near-identical dialogue. Some of the slang terms were updated to make the lines feel more modern, but this is the same movie as was done almost 20 years ago.

The biggest difference here is the cast. Perhaps attempting to appeal to a new demographic all four main characters are now African-American. Surprisingly, all that really changed was the characters’ skin color–the names, actions, and attitudes all mirror those of the white actors in the 80s version. They even work in the same jobs as their earlier counterparts. That this cast happens to be African-American is entirely incidental in this film as directed by Steve Pink (Accepted, Hot Tub Time Machine parts 1 and 2).

The characters aren’t living in Chicago any more, but this movie is a clone of the original.

That said, much like Gus Van Sant’s remake of Psycho, you can take the same script and not achieve the same results. As Danny and Debbie, the main couple, Michael Ealy (Think Like a Man and “Slap Jack” in 2 Fast 2 Furious) and Joy Bryant (TV’s Parenthood) simply lack chemistry. I truly believed every scene between Lowe and Moore in the original, with their complex emotions and conflicting desires. Yet in this remake Ealy and Bryant seem to be going through the motions. Each deliver their lines with feeling, but yet I don’t feel the raw heat that worked so well in the first film.

To make up for this the previously supporting characters of Bernie and Joan have been beefed up. Kevin Hart (Ride Along, The Wedding Ringer) is even given top billing in the credits, though his role of Bernie is only slightly larger than Belushi’s original. Still, Hart is a capable comedian and his Bernie is even better than Belushi’s original. Hart may recycle many of the original film’s jokes but his delivery and timing simply make them funnier.

To continue expanding Bernie’s character a new subplot was added focusing on Bernie’s relationship with Joan (Scary Movie‘s Regina Hall). Belushi and Perkins had sexual tension in the original, but here it’s a full-on relationship that is more fun to watch than the movie’s A-plot.

As I just don’t care about this movie’s Danny and Debbie the remake will never supplant the original for me, but thanks to Hart and Hall I give this film a recommend

March 5, 2015 Posted by Arnie C | Movies, Reviews | About Last Night, Comedy, David Mamet, Kevin Hart, Regina Hall, Romance, Sexual Perversity in Chicago | Comments Off on Movie Review: About Last Night

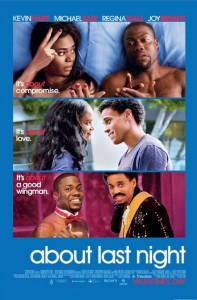

40 Year-Old-Critic: Chasing Amy (1997)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Kevin Smith is a polarizing figure in cinema. The director certainly has his legion of fans, and having attended several conventions with Smith as a featured guest, it seems those fans are mostly male, mostly under 30, and very willing to connect with his characters; lovable losers such as Clerks’ Randall and Dante (Brian O’Halloran and Jeff Anderson, respectively).

I am not in Smith’s camp, and on Now Playing Podcast I have repeatedly expressed my disdain for his body of work.

Yet allow me in this entry of The 40-Year-Old Critic to praise Smith’s best film, 1997’s Chasing Amy.

Amy (as some fans refer to it) was Smith’s third picture. The director was a Sundance phenom with his black-and-white debut (the aforementioned Clerks) in 1994. It did well in theaters and truly found its audience on video — an audience that included me. Thanks to Quentin Tarantino and Reservoir Dogs, I was paying more attention to indie films, especially those heavily promoted by Miramax. As such, I saw Clerks on VHS and enjoyed it.

As I mentioned in my review of Leaving Las Vegas, around this time in my life I was underemployed and frustrated with my lack of career options, so I related heavily to Dante in Clerks. Plus, I was enraptured by the raunchy jokes. Smith raised the bar on profanity with language that originally earned his film an NC-17 rating. As I did with Beverly Hills Cop before it, I laughed loud and hard at Clerks’ envelope-pushing comedy.

Smith parlayed that success into a studio picture, 1995’s Mallrats. The director spent $6 million of Universal Studios’ money on a movie that barely made one-third that amount. Even as a fan of Clerks I thought Mallrats was too cartoonish, too broad. With new lead duo Brodie Bruce and T.S. Quint (Jason Lee and Jeremy London, respectively), Mallrats tried to replicate the bromance of Clerks in a way that felt forced. More, it seemed Smith’s signature characters of Jay (Jason Mewes) and Silent Bob (Smith himself) would not work in color.

Mallrats would not be Smith’s last failure, but it may be his most fortuitous. First, it established his relationship with Ben Affleck, who had a minor role. Second, after Mallrats Smith returned to his “comfort zone” of small, indie filmmaking. On a $250,000 budget — extraordinarily low but still 10 times that of Clerks — Smith wrote and directed Chasing Amy.

By 1997 I was fully indoctrinated into the Cult of Kevin — as rabid a fanboy as any he’s had. I participated in his online message boards and I watched his first two films regularly (and convinced myself Mallrats wasn’t that bad… it is). Whatever Smith made next I would see. Yet the plot of Chasing Amy I found particularly interesting.

Alyssa (Adams) literally comes between Holden and Banky in this scene.

The film centers around two young independent comic book creators, Holden McNeil (Affleck) and Banky Edwards (Mallrats’ Jason Lee). The best friends find their relationship strained when Holden begins a romance with lesbian comic creator Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams; Smith’s then-girlfriend), spurring jealousy in Banky.

To me, the film seemed to be jumping on the bandwagon of “queer cinema” which had started to gain steam in the mid 90s. While mainstream Hollywood acknowledged gay characters in movies like Philadelphia and The Birdcage, it was really indie films that brought them to the fore, with such groundbreaking fare as My Own Private Idaho, The Crying Game, and Kiss Me, Guido.

Specifically, I saw in Chasing Amy echoes of Guinevere Turner’s Go Fish — a film Smith acknowledges as inspiration. Sexual preference felt like an exciting new frontier for films to tackle and, having seen all the ones I just mentioned, I likely would have seen Amy even with a complete unknown behind the camera.

I was actually a bit nervous to see Smith tackling LGBT topics. This was a straight man with a penchant for raunchy humor. In Clerks, for example, lead character Dante slut-shamed and dumped his girlfriend after finding out her sexual history. I wondered if Smith would use Alyssa’s sexuality as a source of humor, or to titillate his built-in male audience.

I was happily wrong. Chasing Amy is an exquisite balance of comedy and drama. The start of the film is right in line with Clerks’ humor, as militant black comic creator Hooper X (Dwight Ewell) dissects the racist undertones of the Star Wars trilogy. It was great fun, like a geeky twist on Tarantino’s Like a Virgin deconstruction in Reservoir Dogs. But the humor is nuanced. It’s quickly revealed that not only is Hooper’s rage an act to sell his comics, but he is also a closeted gay male and close friend of Banky and Holden.

As Holden and Banky, Affleck and Lee created a genuine on-screen friendship. It was one my friends and I related to…until the final twist.

The latter two characters would be familiar to Smith, and not just because both Affleck and Lee appeared in Mallrats. In Clerks, Mallrats, and again here, Smith features the same central duo: immature twenty-something white males with potty mouths. The primary character is more serious, contemplative, semi-neurotic, and dealing with relationship issues. The sidekick is wacky, always given the movie’s funniest lines, but given short shrift in the plot. Here, Holden was our Dante/Quint, and Banky was our Randall/Brodie. The jokes were raunchy and familiar, and the laughs hit hard.

More, Smith seems to know his audience. Any homophobes in the theater get their say through Lee, who spouts gay slurs and stereotypes throughout the film. Featuring gay characters in a positive light, and having Banky spout ignorance, was a subtle way of Smith attempting to educate a more narrow-minded contingent of fans.

Chasing Amy slowly changes tone, though. While all of Smith’s films had dealt with romantic relationships, none had been a romance film. Amy becomes that as Holden befriends unobtainable Alyssa. Their friendship is tinged with longing, and not just on Holden’s side — Alyssa’s feelings for a man make her question her own sexual identity. The scene where Holden confesses his feelings, followed by a rain-soaked argument, is moving and engrossing. There is barely a laugh to be had, and shows a maturity not before seen in a Kevin Smith film.

The film takes continued twists and turns, and jokes keep coming, but Smith had sharpened his humor into a blade, using it to cut the tension of many tense, dramatic scenes. The audience, engrossed in this tumultuous relationship full of self-doubt, would find their laughter a welcome release — the film allowing us to breathe again.

This kiss in the rain was Alyssa finally giving into her feelings for Holden. In most films that would be the end, but here it’s only the beginning of a journey full of self-doubt and jealousy.

While the romantic comedy fan in me was enjoying the Holden/Alyssa relationship, I was also empathizing greatly with Lee’s Banky. I was in my mid-20s and I had lost many friends to their girlfriends. I was all-too-familiar with the pattern of friends who hang out when they’re single, and then don’t return your calls when in a relationship. I saw Banky losing his lifelong friend to a new relationship, and, for the first time ever in a Smith film, I felt bad for the sidekick. Smith had finally created a supporting character with his own arc.

Holden and Alyssa’s relationship eventually hits the rocks when Holden finds out Alyssa was not always gay. The climax (so to speak) comes when Holden, desperate to save his friendship and his relationship, proposes a three-way to both Alyssa and Banky.

That was where the film took things too far. Until that point I felt Smith’s film had portrayed characters acting in ways that felt honest. This twist seemed to be the writer/director choosing to go with a wacky ending over a heartfelt one, or maybe he just wrote himself into a corner and couldn’t find a more earnest resolution.

The group sex idea felt totally outside the realm of Holden’s character. More, that Banky agreed, seemed to me a full character betrayal. I had completely understood Banky’s disappointment with a friend ditching him for a new relationship — it’s a real, common occurrence among single male friends. That Smith chose to write that entire emotion as based in latent homosexuality felt like a missed opportunity — an honest look at friendship was undermined by turning one character into a stereotypical gay male predator.

The film does recover from that moment, with an ambiguous ending that reminded me of The Graduate. Despite my disappointment with the final twist, the movie overall remained an on-screen romance that came across as honest and real. I left the theater entertained and believing Smith would be the next great voice of cinema.

He tried. His follow-up film, Dogma, attempted to analyze religion the way Amy deconstructed relationships, but to lesser effect. While amusing, the picture is scattered and scatological.

But it was with his next effort, Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, that I realized Smith was not an auteur with things to say, but a writer of increasingly insipid comedy. I first saw Smith speak at a convention in 2001, followed by a preview screening of Strike Back, and I realized he was a more amusing speaker than filmmaker.

History would prove that assumption true, as Smith is now an accomplished podcaster, while the best thing I can say about his post-Strike Back films is that there aren’t many of them.

I have seen all of Smith’s directorial efforts, always hoping to see even a hint of the filmmaker that made Chasing Amy. But from Jersey Girl to Zack and Miri Make a Porno to Cop Out and even Red State, Smith has become a serviceable, but completely unexceptional, director of (mostly unfunny) comedies. I would characterize Smith’s later directing work as on par with Tom Shadyac or Steve Carr. If you don’t know those names, you can look them up, but had Smith not been an indie darling in the mid 90s I don’t think you’d know his name either.

I don’t mean that to say Smith is a one-film-wonder, still coasting on Clerks, because I have gone back and watched his directorial debut — it doesn’t hold up. Jokes that pushed the envelope in 1994 now seem almost tame. More, Clerks is less a film than it is a series of sketches loosely tied together. I loved it when I was the characters’ age and related to their Generation X angst, but it is a movie with limited appeal that is quickly outgrown.

I had hoped that after Cop Out’s critical drubbing Smith might — as he did after Mallrats’ failure — return to his roots and make more personal films. That hasn’t happened. While he has done more low-budget films, such as Red State, it appears the filmmaker who made Chasing Amy is gone forever.

It is a shame. With Chasing Amy Smith showed himself to be a talented writer who could balance both comedy and drama with equal measure. It remains a go-to film when I want to laugh, one of the most honest romances caught on screen, and a progressive view of LGBT characters in cinema. Yet it’s the only Kevin Smith film I can recommend.

Tomorrow — 1998!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 27, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Ben Affleck, Chasing Amy, Comedy, Comic Books, Comics, Drama, Enertainment, Film, GLBT, Jason Lee, Kevin Smith, Lesbian, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance, Romcom | 2 Comments

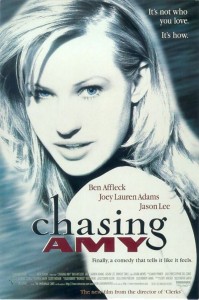

40 Year-Old-Critic: Leaving Las Vegas (1995)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Have you ever had the feeling that the world’s gone and left you behind….

More than any other form of art, films have a soul. Moviegoers can experience a picture on more than an intellectual level; sometimes there is a base, emotional connection. Watching a great film can be akin to falling in love.

This is a view I first articulated while reviewing Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho for Now Playing Podcast (part of our Fall 2012 donation drive, that review is no longer available). That film showed two talented directors could take the same script, sometimes even the same camera shots, and produce different results. One filmmaker created art that engrossed and thrilled audiences, while the other produced a rote, mechanical and generic film.

Tens, hundreds, or even thousands of people — depending on the scope of the production — come together to create a single experience for a viewer. Even I sometimes forget this; the auteur theory takes hold and I focus on the director as sole creator of a vision. While the director usually maintains creative control, sometimes even through the editing stages, the movie itself is the result of millions of little decisions made by every actor, set dresser, composer, editor, and cameraman on the production. With the right people involved even the most mundane script can become a memorable experience.

One prime example of such a script elevated by those working on it is Leaving Las Vegas, the 1995 drama directed by Mike Figgis, starring Nicolas Cage and Elisabeth Shue. On paper, this movie seemed like the most trite of stories — depressed drunk Ben Sanderson (Cage) is a Hollywood screenwriter whose penchant for drink has ruined his every personal and professional relationship. When he is finally fired from his job he is ready to die, so he takes the last of his cash to Las Vegas where Ben plans to drink himself literally to death. In Vegas Ben hires a prostitute Sera (Shue), the damaged hooker with a heart of gold. The two lost souls fall in love, yet neither is willing or able to change their self-destructive habits.

These character tropes are so hackneyed that I would expect this to be a film made in the 1930s, when stories and characters were broader, and not the 1990s.

Cage in one of his more charming scenes, back-lit by the lights of the Vegas strip.

The film is based on a novel by John O’Brien. I have not read that book, but I have no doubt of O’Brien’s commitment to the material. Two weeks after discovering Leaving Las Vegas was to become a film, O’Brien used his gun to commit suicide. Clearly this was a man who understood the struggle with depression and the impulse to kill yourself. Yet, despite the insight his prose may offer, I have no interest in reading a book about two stereotypical characters going through a depressing endeavor. It may be very well written and I may be missing out, but the story itself sounds uninteresting.

Yet, despite cliched characters and a tired plot, in the hands of these filmmakers the result is a dramatically moving experience. Few movies I’ve seen in my life parallel the emotions stirred in me by Leaving Las Vegas, for what this team did, through filming and editing, was craft a film where the plot matters less and the characters matter more.

The tale is about a drunk, and the editing and filming often give the film a fugue-like ambiance. Sometimes the dialogue is crystal-clear, loud and in full focus. Other times the music mix raises. Sometimes you hear nothing as the actors’ lips move, other times there are words but you cannot make them out. It’s a dream-like experience that reminds me of techniques used by David Lynch.

The impact of the music cannot be overstated. The score, composed by Figgis himself, sounds like music played around 2 a.m. at an upscale bar. Heavy with piano and saxaphone, the music has a slow jazz feel that underlines the emotions of the moment. More, in an unusual move, some of the score is lyricized and sung by Sting. It blurs the line between soundtrack and score, but in the process creates sorrowful ballads of love and loss. Those original compositions intermix with covers of classic songs, such as “Lonely Teardrops” sung by Michael McDonald.

The sounds of the street often drown out character dialogue, to great effect.

The result sometimes feels like a depressing music video or an “in memoriam” montage, played while the characters still live. That Figgis is so willing to part with dialogue and just convey mood shows that in Las Vegas plot doesn’t matter. This is a character-driven story and we don’t need to hear their words to feel their pain.

This type of disregard for traditional narrative is used at the micro and macro scale. Sometimes the film cuts to the future suddenly, and we return to the present when Ben comes out of his stupor. We learn about the missing moments when Ben asks what happened. This is a movie told primarily from Ben’s shaky, out-of-focus point of view, and the camerawork and editing embody that mindset.

More than the cinematography, this film hops in and out of Ben’s own head. Sometimes we see Cage saying outrageous things, but then we discover it was only a fantasy in the character’s mind. In contrast, sometimes Ben makes equally offensive statements out loud and faces the very real consequence. As his blood alcohol content rises Ben cannot distinguish reality from fantasy, and, like Ben, the audience never knows exactly what is happening and what we can believe.

Of course, Figgis could not accomplish this alone. In the hands of a lesser actor than Cage Leaving Las Vegas could become an unintentional comedy quickly forgotten. Now, 20 years later, Cage is often disregarded, written off due to a long string of bad movies in which the actor makes unfortunate character choices.

Cage is an actor who gets off on playing characters in unconventional ways and giving them strange mannerisms. Often that will alienate the audience, but in Leaving Las Vegas Cage commits totally to the role. His body language exudes desperation. In one of the movie’s first scenes Ben is unintentionally sober, craving drink, and hitting up some colleagues for cash. He comes off sweaty, clumsy, and off-putting. One scene later, after a few drinks, Ben has an undeserved, over-inflated sense of self-confidence and makes improper advances on an attractive woman at the bar. It’s a wild swing of character, and is played perfectly through Cage’s intonation, eye work, and mannerisms.

This type of character could alienate audiences. Had viewers seen Ben as more creepy than sympathetic the result could be quite different. It’s little moments Cage plays, such as sobbing “I’m sorry” when being fired, that show humanity in this sad soul. It makes him someone we feel for, rather than pity.

I was a fan of Cage’s coming into Leaving Las Vegas, with Guarding Tess, Trapped in Paradise and Wild at Heart as highlights (though I’d also suffered through Kiss of Death, It Could Happen to You, and Amos & Andrew). Cage often gave captivating performances, but none I’ve seen before or since match his Oscar-winning performance here.

Despite how they meet, the relationship between Ben and Sera is about love, not sex.

Matching Cage’s portrayal is co-star Shue. In her roles in Back to the Future 2, Adventures in Babysitting, and even Cocktail I’d found the actress to be capable, but unexceptional. As Sera, Shue shows a range I’d never seen before. Early in the film Sera is a hooker, and very good at her job — she instinctively knows what the John wants, and becomes it. With Ben we see Sera start to open up. She lets down her guard, takes off her make-up, and becomes a real person. The transformation is startling, as is Shue’s lack of vanity in several unflattering scenes.

But Sera is not your normal streetwalker — she also has regular visits to a therapist. In these scenes we get to see inside Sera’s thoughts through monologues, confessions taken from her therapy session. As edited, these moments play like scenes from the confessional booth in MTV’s The Real World, but without them we would never be able to trust Sera. We never see the therapist; Shue is giving brief one-woman performances, but conveying pure emotion. This is a challenge for any actor, and she pulls it off. Shue fully deserved her Academy Award nomination for this performance.

Together Cage and Shue create a wholly believable, wholly dysfunctional, couple. Both broken characters are instantly drawn to the other. Though Sera knows Ben may be trouble, she puts that aside and chooses to follow her heart. The film avoids making their relationship too gross or base by actually, and believably, removing sex from the equation–while Ben hired Sera for physical gratification the liquor prevented him from performing. He becomes the only character not sleeping with Sera, even choosing to sleep on the sofa at night despite Sera’s repeated offers of more.

These two share a chemistry and a spark on screen that few romantic films can match. Though it’s a futile hope, it’s easy to root for these two to overcome their hardships through their new-found love.

Those two actors are the primary cast but even the minor roles are perfectly played by actors you’ll recognize; from Steven Weber (Wings, Stephen King’s The Shining), to comedian Richard Lewis, to Laurie Metcalf (Scream 2, Roseanne). It could almost be a drinking game — take a shot when you see an actor you know. With French Stewart, Shawnee Smith, R. Lee Ermey, Mariska Hargitay, and even, in the thankless role of bank teller, License to Kill’s Carey Lowell, you would be as drunk as Ben when credits roll.

No one on screen breaks the mood. Figgis has created his own Vegas, sometimes romanticized, sometimes demonized, but always real.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Yet to take that interpretation is to miss several important details. Sera is, in many ways, a mirror of Ben. Both came to Vegas from Los Angeles. Both are recently unemployed (Sera finding herself without purpose when Yuri, her lover and pimp played by Julian Sands, is murdered by Russian mobsters). Both characters are deeply wounded and on dangerous paths. And both accept each other unconditionally; Ben’s condition of being with Sera is that she never ask him to stop drinking. Likewise, Ben is accepting of Sera’s profession, knowing that she will continue to hook while he lives with her.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

The star of the movie is clearly Cage as Ben, but every time I watch this film I become more convinced the true main character is Shue’s Sera. And it is through Sera that I found my own redemption in 1996.

That summer I had graduated college. My Communications degree and B-average in were not opening any doors. I had a small apartment in a boring town. Most of my friends had left for bigger cities and greater opportunities. My full-time job was working nights as tech support for an Internet company. It didn’t demand much; I sat alone in an abandoned building for eight hours a day, answering the phone on the rare occasion that it rang. It also didn’t pay much; I was living on $8.25 per hour.

Not that I had career aspirations. In college I spent my time doing my coursework and never got to the other things I wanted to do — write some screenplays or even publish some short stories. I had nothing to build my resume, and no idea what career path I should take. I still wanted to entertain people — that drive instilled since seeing Pump Up the Volume — but come fall, even my gig as a DJ would be taken away.

Despite having family living in my same town, we were never close. I preferred being alone in my dark apartment to spending time with them (and I loathed being alone). I was so desperate for friendly contact that, despite having graduated, I asked my college radio station if I could continue to work (for free) as a DJ through the summer.

Mostly, I was lonely. While friends would have alleviated this problem, to me the solution was a girlfriend. Many of my college friends had married soon after graduation. It is very easy for a lonely straight man to envision a woman as the answer to his troubles, and I certainly fell into that mindset. Yet with few friends, no social events to attend, and Internet dating not yet commonplace, I had no way to even meet a woman unless she happened to be delivering my pizza one Friday night.

With all these troubles, no money, few friends, bad job, no prospects, I was suffering from a deep depression.

I was never suicidal, but my overriding emotion was one of apathy, with a side of hopeless despair. My only pleasure in life came from movies. I couldn’t afford to see many in theaters, but I spent what little surplus income I had at the rental store week after week.

Ben’s constant fight against DTs show alcoholism isn’t a glamorous way to die.

That was when I found a kindred spirit in Ben Sanderson. Despite having recently turned 21, I was never much of a drinker. Still, there was something romantic in the very notion of going to Sin City and dying through copious consumption.

Yet through this act of destruction, Ben found his “angel” in Sera. And despite connecting with Ben’s depression, in Sera I saw strength and hope. Sera was in an equally bad situation — her “career” was short-term and dangerous. She was a smart, attractive woman, and even the Vegas cabbies were telling her she could do better than her station in life. When the movie ends Sera loses her love but gains hope for a brighter future.

Through Leaving Las Vegas’ trippy mood, moving characters, and tale of redemption I found my own. I was inspired out of my funk. Nothing happened quickly, but over the next four years my ambition redoubled, I went back to school to get a more employable degree, and I met my wife. But when my future seemed nearly as bleak as Ben’s, Leaving Las Vegas showed me the neon light at the end of a tunnel.

I believe that connection is partially because of the tragic, sad story presented, but the experience is heightened by Figgis’ choice to drop out dialogue and scenes. Figgis’ music created an emotional call-and-response; when the film’s dialogue was drowned out my own struggles filled in the blanks. When the dialogue faded out I would project my pain into the film, mixing with Ben and Sera’s until we were indivisible.

Even today, as I live a much happier, optimistic, and realized life, the film still moves me. You don’t have to be in pain to empathize with those in pain; you don’t have to hear their words to know their struggles.

This is where Leaving Las Vegas transcends being a movie and becomes a full, engrossing experience. This is the soul of a film.

Tomorrow — 1996!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 25, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 1995, 40-Year-Old Critic, Alcohol, Alcoholic, Drama, Elisabeth Shue, Enertainment, Film, Las Vegas, Leaving Las Vegas, Mike Figgis, Movie, Movies, Nicholas Cage, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance | 1 Comment

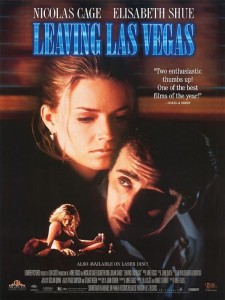

40 Year-Old-Critic: When Harry Met Sally (1989)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

On Now Playing Podcast my co-hosts Stuart and Jakob often joke about my affinity for romantic comedies, or “RomComs.” I don’t mind the jokes. After all, it does seem that I tend to go to this lighthearted genre whenever discussing works of actors and filmmakers.

A History of Violence star Maria Bello? First saw her in Coyote Ugly and loved her in The Cooler.

I researched the work of The Wolverine director James Mangold by watching the atrocious Kate & Leopold.

Even mo-cap pioneer Andy Serkis — we actually see his face in 13 Going on 30.

The list goes on and on. I never analyzed my proclivity for these films, but the repeated jesting had me reflect a bit on why I spent time watching them in the first place. It quickly became clear that I chose to see those movies and more because of When Harry Met Sally.

When Harry Met Sally was released in the summer of 1989, which, at that point, might have been the biggest moviegoing summer in Hollywood history. Films like Star Trek V, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Batman, Ghostbusters II, and Back to the Future Part II were all unleashed within weeks of each other.

With these blockbuster heavy-hitters on the calendar, Rob Reiner’s romantic comedy was not the No. 1 film on my “must see” list, but it was up there.

Crystal, Kirby, Fisher, and Ryan engage in 4-way split-screen action.

Part of the draw was the talent involved. I had liked Meg Ryan in Innerspace, and, although I was too young to appreciate the genius of Soap, Billy Crystal had really impressed me with Throw Momma from the Train.

But the biggest draw was Reiner. While I grew up watching “Meathead” on All in the Family, I’d already come to respect him as a director after seeing Stand by Me, The Princess Bride, and even the John Cusack comedy The Sure Thing.

Also, if I’m going to be completely honest, there was another big draw: Sex.

I was in my early teens and dating was a frustrating, confusing experience. I was also learning about sex through government-mandated public school health class as well as… extracurricular materials. As a boy desperately wanting to gain insight into the female brain, this film seemed like a wealth of knowledge.

The trailers teased wise phrases such as “Men and women can’t be friends, the sex part always gets in the way.” Was that true? It boggled my adolescent mind to ponder.

And there was the clip of Meg Ryan performing Sally’s fake orgasm in Katz’s Delicatessen. Yeah, I really wanted to know more about that!

Getting into the theater was a tricky proposition for someone three years shy of the 17-year-old threshold for R-rated films. I eventually convinced my prudish 21-year-old sister Michelle and her husband to take me.

I know that at 13 I didn’t get all the jokes or understand the subtle nature of some of the humor (I also totally didn’t recognize “Princess Leia” Carrie Fisher as Sally’s best friend Marie). Still, I was taken by this film and its world.

Crystal was funny and salacious as Harry. I was won over by this libidinous lothario early on, during the car ride when Harry propositions Sally despite the fact that he’s dating her best friend. Crystal’s timing is spot-on. In the hands of another actor this type of introduction could have alienated the audience, but Crystal’s light hearted delivery, his sparkling eyes, and his disarming smile made Harry the type of character men could root for and women could come to love.

As Sally, Ryan gave the performance of her life. I developed a major crush on Sally and, due to this, I saw most of Ryan’s work. The success of this film made her a hot property, but from Flesh and Bone to I.Q. to The Doors, no performance she has ever given comes close to matching the one she gives here.

I believe part of this is because of the way Ryan threw herself into the role, right down to the deli orgasm scene. While some actresses may have shied away from such an extreme moment, this scene was actually Ryan’s idea. With physical comedy, self-effacing stumbles, and great delivery, she gave her all to When Harry Met Sally.

More, I think her co-stars, primarily Crystal and Bruno Kirby, were so amazing that Ryan’s game was elevated.

Thanks to the performances from the two leads and a script by Nora Ephron, Reiner created the perfect romantic comedy; one that appeals equally to men and women. The movie delicately balanced the two points-of-view and at no point while watching When Harry Met Sally did I feel I was watching a “chick flick.” To me it was just a comedy film.

Not only did this film make me fall in love with Sally; I fell in love with New York City. This was the first time I’d seen New York truly romanticized on screen. Sure, Ghostbusters, Splash, and Short Circuit 2 were among the many movies set in the Big Apple, but this film truly drove home to me the differences between New York and other cities where I’d spent considerable time, such as Chicago or Fort Myers, Florida. The use of cabs for transportation, the unlikely experience of running into old acquaintances in a city with 8 million residents, the difficulty of taking home a Christmas tree in a town that relies on public transportation — I saw it all for the first time in When Harry Met Sally. This was the first movie that I realized to be as much about a place as the people.

Reiner deserves so much praise for the way he structured the film; using holidays to show the passing of time, the split-screens during the four-way phone call, the rapid-fire quips — honestly, I could gush about this film for pages. It is one of those movies that just came together and made on-screen magic.

When Harry Met Sally is the perfect movie to watch between Christmas and New Year’s–a perennial holiday favorite.

This was my first foray into truly adult comedy, as compared to the Eddie Murphy comedy that just used adult language. When Harry Met Sally has adults dealing with issues of age, marriage, and commitment; and doing so in a funny way.

I left the theater still pondering the question of whether men and women can be friends; but I was certain that, through Sally, I’d gotten a glimpse into the workings of the fairer gender. I certainly didn’t know all I needed to know, but I felt that I’d been educated (through the film’s female perspective) as well as entertained (by the film’s male point of view).

I wanted to know more, and I wanted to laugh as hard as I did in that theater. Because When Harry Met Sally was such a success, the comedies of the 1990s and 2000s kept copying Reiner’s formula, and I watched dozens of them hoping to feel the same as I did in 1989.

I followed Ryan to French Kiss, Sleepless in Seattle, Addicted to Love, and many more hoping to see, but never finding, the magic she possessed as Sally. Only You’ve Got Mail came close.

I also followed Billy Crystal to the forgettable Forget Paris, but enjoyed his comedy more in City Slickers and Analyze This.

When neither Crystal nor Ryan repeated their success I tried to find this type of on-screen chemistry with other known actors. From Sandra Bullock and Bill Pullman in While You Were Sleeping, to Nicholas Cage and Bridget Fonda in It Could Happen to You, to several Friends stars in films best forgotten, I watched them all.

Most of them were terrible.

Not only did these movies lack the insight and wit of When Harry Met Sally, the genre itself slowly degenerated before my eyes. Initially the films would try to replicate Reiner’s delicate balance of romance and comedy, but in time they changed to focus far more on the romance, less on the comedy, becoming base female wish fulfillment. By the mid-90s the vast majority were, indeed, the “chick flick RomComs” that Jakob taunts me for watching. There were a few gems in the bunch, such as The Wedding Singer, There’s Something About Mary, Bridget Jones’ Diary and The 40-Year-Old Virgin, but, by and large, they were junk that left me bored.

But if I was not entertained, was I educated? Did this deep dive into the world of female-targeted cinema give me insights into women? Well, in the past 25 years I’ve learned a lot, and mostly it’s that everyone is a unique individual. My quest to learn some magic secret about “all women” was doomed to fail because each woman is her own person. I learned that not through film, but through dating and, eventually, marriage.

I also learned the answer to Reiner and Ephron’s main question — yes, men and women can be friends. The best marriages are those where the two are friends. I feel lucky to have that where my best friend is my wife.

So maybe When Harry Met Sally taught me something after all.

Tomorrow: 1990!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 19, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1980s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Billy Crystal, Bruno Kirby, Carrie Fisher, Comedy, Meg Ryan, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Orgasm, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Rob Reiner, Romance, Romantic Comedy, Romcom, When Harry Met Sally | Comments Off on 40 Year-Old-Critic: When Harry Met Sally (1989)

Movie Review: Kate & Leopold

This was released on Christmas Day…I’d have preferred the lump of coal.

Today The Wolverine opens in US theaters. Excited for this next film in the X-Men saga I watched Kate & Leopold, a 2001 romantic comedy starring Meg Ryan and Hugh Jackman.

No, I wasn’t just going to watch any Jackman film; Kate & Leopold is directed by James Mangold, and based off their working relationship in this film Jackman tapped Mangold to direct The Wolverine when first choice Darren Aronofsky dropped out. Jackman has said in interviews this decision was based largely off their relationship founded during Kate & Leopold.

While Mangold has done many other respected films, including award-winning Walk the Line, Girl, Interrupted and 3:10 to Yuma, plus the Tom Cruise action/comedy Knight and Day, I wanted to see this Jackman-Mangold time-travel rom-com collaboration to set my expectations for The Wolverine. Would I see something in Kate & Leopold, a spark of creativity, a visual flare, that would show Mangold a good fit for a high-octane comic book film? Would Jackman’s performance be one no other director had been able to get from the actor? Would I see anything in this film to indicate through style or sensibility that Mangold was the man to give fans, as the TV ads state, “the Wolverine film you’ve been waiting for”?

Having now seen Kate & Leopold I certainly hope not.

Jackman stars as Leopold, a 19th century Duke and future inventor of the elevator (which, the credits admit, is not historically accurate). With his family fortune dwindling Leopold is forced to take a wealthy wife, though Leopold has never loved anyone. But at the party where his engagement will be announced Leopold spots Stuart (Liev Screiber)–a strange, shifty man carrying a miniature camera.

Stuart is actually Leopold’s great-great-grandson from present day New York City. Through the laziest time travel explanation ever (he just jumped off a bridge), Stuart came back in time to see his ancestor. But Leopold gives chase and both he and Stuart arrive in 21st Century Manhattan. There, Leopold meets Stuart’s ex-girlfriend Kate (Ryan), a cynical, bitter, career-minded woman, working in market research. Eventually Kate’s resistance melts and she falls in love with the Duke, but Leopold must return to his own time lest a paradox remove all elevators from modern life.

From the trailers and description, I expected Kate & Leopold to be a version of Back to the Future. Jackman plays a man unfamiliar with modern technology and customs, so the obvious plot would be that his focus is to return home while also falling in love. Plus the ancient-man-in-modern-times concept has many opportunities for hilarity, as seen in Jean Renot’s The Visitors.

But under Mangold’s direction Kate & Leopold eschew most all attempts at comedy or realism. The film is a banal romantic fantasy tailored for aging, lonely women. As Leopold, Jackman is polite, charming, and handsome. More, his every attention is given only to Kate–he has no job, no friends, nothing else to occupy his time; Kate is the center of his world. He makes her breakfast in the morning, does her dishes in the evening, and stands up when a lady leaves the table. Leopold doesn’t even seem to want to return to his own time, he’s happy to just stay in the future, living in Stuart’s apartment and romancing Kate.

In Ryan’s introductory scene she is doing market research on a rote rom-com which isn’t working. The researchers think the female lead is unlikeable, and the film’s director exclaims that marketers are sucking the soul from the art of film. That is certainly true of Kate & Leopold. The entire film is so obvious it is set to play to a test audience of the least sophisticated of Americans. An audience with expectations set so low as to simply find comfort in the familiar.

And a romantic comedy with Meg Ryan as the female lead is nothing if not familiar. Here, in the waning years of her popularity, her face taut and lips inflated by the work of a plastic surgeon, Ryan is breaking no new ground. Her character Kate observes a neighbor who plays the soundtrack for Breakfast at Tiffany’s every night, and the same can be said for much of Ryan’s career, stuck in an endless loop of interchangeable roles as a romantic lead. Certainly she does nothing here to broaden the range of her characters.

I am a fan of escapist fantasy, but Kate & Leopold is too obvious in its pandering, and painful to watch in that it ignores its own ironies. Kate broke up with Stuart because he was an unemployed dreamer, yet she falls in love with his ancestor who is just a more romantic version of that same persona. More, as Kate eventually travels back in time to marry Leopold, the film glosses over the icky fact that for four years Kate was sleeping with Stuart, her great-great-grandson!

The film does have several chase scenes, such as Leopold running down a mugger in Central Park and Kate having to rush to travel back in time before the portal closes. Under Mangold’s direction these scenes have no spark to them. They feel obligatory, not exciting. Kate and Leopold stole the plot from Back to the Future’s climax, but got none of its excitement.

This film is not recommended for any but the loneliest of spinsters who want to dream of finding love before their lady parts dry up.

And Kate and Leopold has given me a feeling of trepidation as I prepare to see The Wolverine. There is no doubt Jackman made friends while hanging out on sets leftover from Gangs of New York–Schreiber would play his “brother” Sabertooth in the first Wolverine film; Mangold would direct the second. But in a film this unoriginal I see nothing that makes me think Mangold is a fit for The Wolverine.

But we will find out! You can hear Now Playing’s review of The Wolverine on August 13th at NowPlayingPodcast.com

July 25, 2013 Posted by Arnie C | Comic Books, Marvelicious Toys, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 2000s, Comics, Hugh Jackman, James Mangold, Marvel, Meg Ryan, Now Playing, Review, Romance, Romantic Comedy, Romcom, Time Travel | Comments Off on Movie Review: Kate & Leopold

-

Archives

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (2)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (2)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Site info

Venganza Media GazetteTheme: Andreas04 by Andreas Viklund. Get a free blog at WordPress.com.